Boyan Nikolaev is deputy executive director of KRIB. He graduated in business administration from City University of Seattle and holds a PhD in public communications from New Bulgarian University. He teaches at the Department of National and Regional Security at the University of National and World Economy and at the Department of Media and Communications at New Bulgarian University. He is an advisor to the President of the Irish-American University in Dublin.

The greatest contemporary libertarian economist, Murray Rothbard, wrote in 1995 that the title “father of modern economics” should not be held by the ubiquitous Adam Smith, but by a little-known Irish merchant, banker, and adventurer who wrote the first treatise on economics more than four decades before the publication of Smith’s The Wealth of Nations. This was Richard Cantillon, who lived a turbulent, Hollywood-esque life and, after staging his own death in a fire, disappeared without a trace forever.

Cantillon left us a single surviving work, “Essay on the Nature of Trade,” in which we can find the answer to why inflation problems today are found in countries outside the eurozone rather than within it.

An answer that has been known for 300 years as the “Cantillon effect.” At the very beginning of the 18th century, the Irishman made a very insightful observation that when new money enters the economy, it is not distributed evenly among all people and companies.

He gave the example of the sudden discovery of a large gold deposit, which produces money that flows into the economy but first ends up in the hands of the mine owners and the miners working there before reaching everyone else. Suddenly, people who have become rich with new money will want to buy more wine and meat, abandoning their traditional diet of bread and beer.

Noticing this, local farmers will abandon grain cultivation and immediately direct their investments to livestock, vineyards, and farms. The poor peasants, far removed from all these processes, may suddenly find themselves in dire straits and become even poorer—first, because farmers will produce less bread and grain, and grain, which will become more expensive, and secondly because the prices of wine and meat will skyrocket so high that they will no longer be able to afford them at all.

This simple example from three centuries ago shows why today the pace of price increases in the heart of Europe is much calmer than the inflationary storm raging on the periphery outside the eurozone. Today, new money in the eurozone is not created by sudden discoveries of precious metals, but by the government spending of large governments and the lending of large banks, backed by the European Central Bank or by technology companies and innovations whose stock market breakthroughs enrich their shareholders. Thus, citizens of large eurozone countries, shareholders in investment funds, banks linked to the European Central Bank, and industrialists with direct access to low-interest euro loans are the first to receive the new money and buy food, machinery, software, hardware, and other assets at current prices. This is noticed by large retailers, resellers, machine manufacturers, and even farmers, who immediately direct their supplies there, readjusting their production chains to serve the heart of Europe. A little later, the increased money supply leads to a cascade of price increases.

The periphery waits for the new money to reach it, watching helplessly as food prices and production assets jump with each passing month. It even waits for geographically simple goods to reach it with a delay – be it French cosmetics, liquid chocolate, Italian clothing, or industrial robots for heavy industry. And waiting costs money, both in lost profits and higher costs.

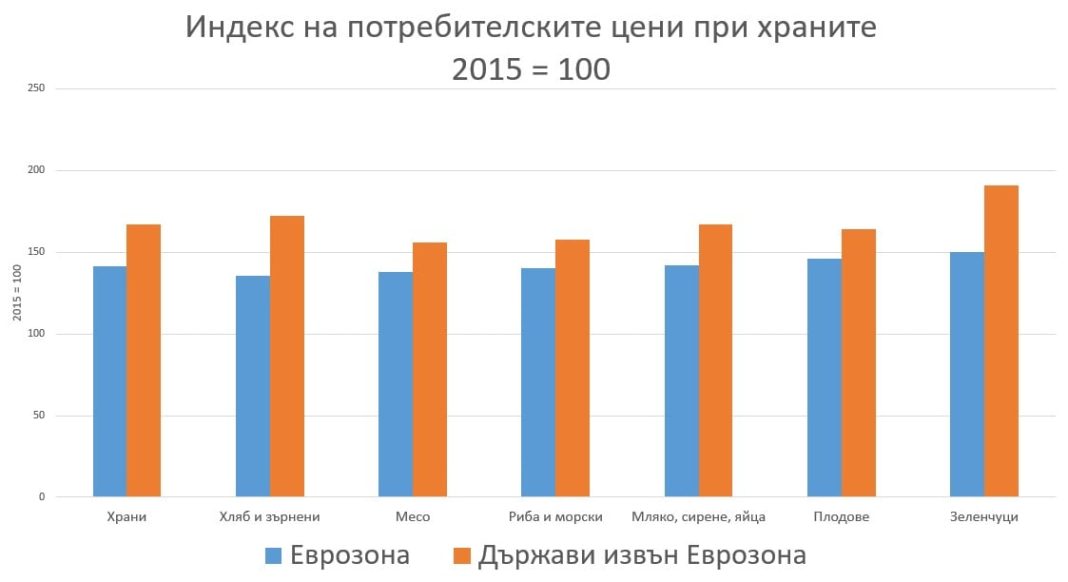

This is not a complex and abstract theory, but prices that we all see in the supermarket and that industrialists see in offers for machines, robots, and software. There is hardly a Bulgarian who has not been stunned at least once a week for the past two to three years by the fact that a small 90-gram chocolate bar costs nearly 5 leva, while the same bar in Germany remains stubbornly at 1.3 euros; how liquid chocolate is 18 leva, while in Germany it has not budged from 6 euros; how first-class tuna in Bulgaria is approaching 60 leva, while the same in Brussels is 27 euros. All these figures are clearly visible in Eurostat’s food statistics – the inflation rate in the eurozone is lower than the average for all EU member states outside the euro.

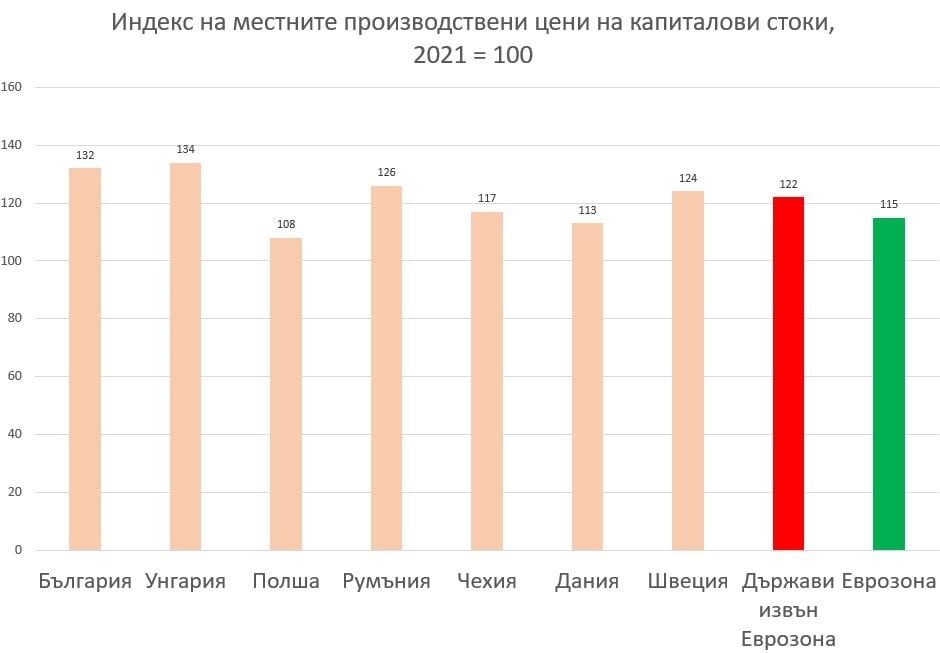

The situation is no different for industrialists outside the eurozone – price increases are faster and more chaotic than in the heart of the eurozone, and this is particularly true for Hungary and Bulgaria:

Industrialists and entrepreneurs in countries outside the eurozone have another problem: by valuing their assets in relatively little-used local currencies, they find it much harder to attract investment capital. It is no coincidence that Bulgarian unicorn companies are looking for investors on the Frankfurt Stock Exchange and even in the US, which is precisely such a point of injection of new money into the economy. Entrepreneurs are voting with their feet and their money, offering their companies’ shares in the major financial centers in euros and US dollars—if small currencies were so competitive, German start-ups would be coming to Sofia, not the other way around.

Some intelligent opponents of Bulgaria’s entry into the Eurozone put forward philosophical arguments about the nature of fiat money, budget deficits, and the direct monetization of debt around the world over the past 50 years. But Bulgaria, with a share of the economy of less than 0.1% of the world’s, using the Bulgarian lev, whose share of international SWIFT transactions is 0%, will not single-handedly change the international financial and monetary system today. On the contrary, today we are colonially tied to this system through the euro, without even a theoretical voice in its governance.

If we remain on the periphery, we will continue to be hit by waves of inflation as consumers; we will queue up to buy machines as industrialists; we will spend huge amounts of money on offshore offices and financial consultants to offer our shares in the euro capitals as entrepreneurs. And we will light candles hoping that the next recession does not hit the financial sector, because without access to the European Central Bank, the only resource available to support our banks and economy is the savings and taxes of Bulgarians.

It is far better to enter the heart of Europe, where new money will reach us on an equal footing with the Germans and the French, food prices will rise more slowly, and businesses will have faster access to cheaper assets. And from the conference table of the European Central Bank, the governor of the Bulgarian National Bank will be able to propose solutions for changing the global financial and monetary system with a real chance of them becoming reality.

Translated with DeepL.

Източник: Economic.bg